Strategic fit is a crucial concept in business strategy that refers to the alignment between a company’s internal capabilities and resources with the opportunities and demands of its external environment. The contrasting fortunes of IndiGo and Jet Airways in the Indian aviation industry provide an excellent example of the importance of achieving strategic fit for long-term success in a competitive market.

Strategic Fit Overview

Strategic fit is the degree to which a company’s strategies, objectives, and capabilities correspond with and support one another, as well as align with the external environment. It is a measure of how well an organization’s activities support its overall strategy, helping firms make better decisions, allocate resources efficiently, and create a competitive advantage.

Strategic fit can be categorized into three main types: management fit, market-related fit, and operating fit. Each type focuses on aligning different aspects of an organization’s internal capabilities with its external environment.

- Management fit ensures that management practices, decision-making processes, and organizational culture are aligned with the overall strategy. This includes having the right leadership team in place, fostering a culture that supports the strategic objectives, and ensuring that management decisions are consistent with the company’s direction.

- Market-related fit aligns the company’s market strategies, product offerings, and customer segments with the needs and preferences of the target market. This involves understanding customer requirements, competitive dynamics, and market trends, and adapting the company’s approach accordingly. For example, IndiGo’s focus on the low-cost carrier model and targeting price-sensitive customers has helped it achieve a strong market-related fit in the Indian aviation industry.

- Operating fit ensures that the company’s operational processes, resources, and capabilities support the strategic objectives. This includes optimizing supply chain management, production processes, and resource allocation to deliver products or services efficiently and effectively. IndiGo’s single aircraft type strategy, which minimizes maintenance and training costs, and its focus on high aircraft utilization and quick turnaround times, demonstrate a strong operating fit.

IndiGo vs. Jet Airways

Let us take up a short case study of the Indian Aviation Sector, with example of two airlines – one is Jet Airways which has failed and other is Indigo which holds 60.6% Market share in the domestic market with an on-time performance of 76.1%.

But why did Jet Airways fail whereas indigo airlines became the market leader?

For this, let us rewind into the 2005 – 2006 – on the 16th of June 2005, the fourth day of the 46th Paris Air show, Airbus made a stunning announcement – that an upcoming airline by name of Indigo had ordered 100 Airbus 320 family aircrafts. The deal was worth nearly $6 Billion at list price. Stunning and audacious – forget ordering, no airline in India had even thought of ordering so many aircrafts till then.

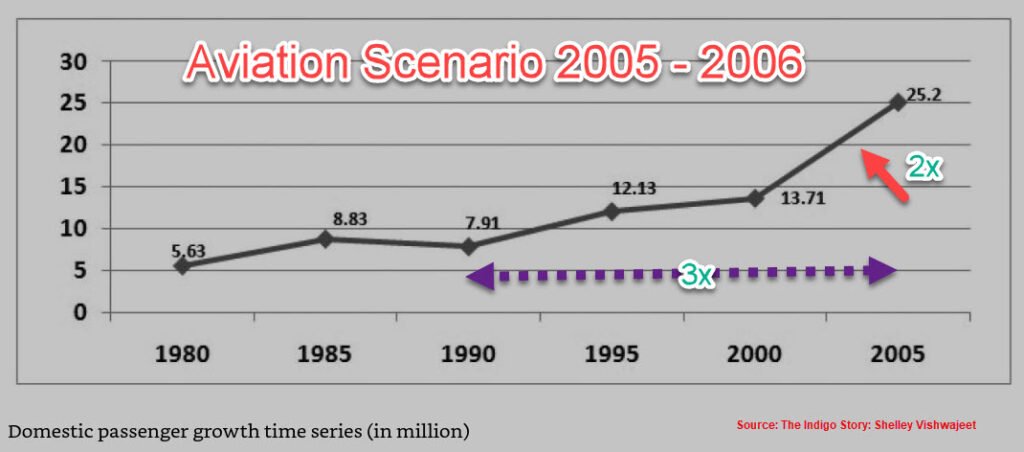

The Aviation scenario – 2005 – 2006

Indigo arrived on the scene, almost 14+ years post liberalization. The Indian aviation sector had undergone significant change – the air traffic had doubled between 2000 – 2005 itself. The share of Private carriers was increasing as you can see from the picture, from 42.9 percent in 1996 to 67.5% in 2005 – 06.

Regulatory developments

In 2004 Government announced the 5/20 rule – which meant that to compete internationally, the airline had to complete 5 years and have a 20 aircraft fleet as a minimum to begin their international operations. This had deep implications for fair competition. The rule acted as a safety net for the national carriers as well as a cushion for to early operators like Jet Airways – because it prevented immediate competition. By 2005, only two private airlines, Jet Airways and Air Sahara had been given permission to fly to international destinations.

Kingfisher was in a hurry to start international operations and probably that proved to one of the reasons for its failure. In this pursuit, it stretched itself to acquire Air Deccan, which by then had become eligible for international operations by the virtue of its establishment in 2003. Vijay Mallya’s Kingfisher acquired Air Deccan at a price much higher than its real market value. Financially, this stretched Kingfisher. The 5/20 rule remained a bone of contention for the operators till June 2016 – when this rule was converted to 0/20 by the Modi Government.

Political

In 2004, Dr. Manmohan Singh took over as the Prime Minister of India, and there were high expectations due to his reputation as the “author of the new economy” during his tenure as Finance Minister under the PV Narasimha Rao government (1991-95). It was widely believed that this liberal economist would adopt policies that favoured free market competition and were less protective of government enterprises. While there was policy stability, the aviation sector encountered its own set of challenges due to the pressures and compromises of coalition politics.

Competition

When IndiGo began its operations, only two airlines from the early phase remained: Jet Airways and Air Sahara. However, Air Deccan, India’s first low-cost airline founded by Captain Gopinath, was leading the market. Established in 2003, Air Deccan had captured a 19% market share by the end of 2005, operating flights to 55 destinations with a fleet of 30 mixed-type aircraft. Despite its market presence, Air Deccan struggled with poor on-time performance and substandard customer service. In 2008, it was sold to Kingfisher Airlines and rebranded as Kingfisher Red, the low-cost arm of Kingfisher Airlines.

Then there was Modi Luft, which began operations in 1993 but was grounded in 1996. In 2004, it was taken over by a consortium of investors led by London-based Indian businessman Bhupendra Kansagra. Ajay Singh, the current promoter and chairman of SpiceJet, was also a key member of the team. The airline was rebranded as SpiceJet, a low-cost carrier that commenced operations in May 2005.

Sahara Airlines, also known as Air Sahara, was one of the early entrants in the Indian aviation market and had ambitious plans, as the group typically did. However, its financial situation was always precarious. In 2007, Jet Airways acquired Air Sahara, which helped Jet Airways achieve a commanding market share of over 30 percent but also led to significant financial strain. Following the management change, Air Sahara was rebranded as JetLite.

Meanwhile, GoAir, the low-cost airline from the Wadia group, entered the market in November 2005. Led by Jehangir (Jeh) Wadia, the younger son of Nusli Wadia, GoAir adopted a strategy of slow and steady growth. By the time IndiGo launched, seven major airlines were ready to compete: one government airline—Indian Airlines, three full-service private airlines—Jet Airways, Air Sahara (now JetLite), and Kingfisher, and three low-cost carriers—Air Deccan, GoAir, and SpiceJet. IndiGo appeared to be the weakest of them all.

Jet Airways, renowned for its excellent service and professionalism, earned significant respect for private airlines and played a pivotal role in transforming Indian aviation. Since its inaugural flight in 1993 from Mumbai to Ahmedabad, the airline’s growth was impressive, quickly challenging government carriers Air India and Indian Airlines (later Air India Express) for market share. At its peak, Jet Airways commanded immense respect, held the largest market share, and was the preferred choice for corporate travellers, dominating metro routes and particularly excelling on the premium Delhi–Mumbai route. Additionally, Jet Airways was the first private airline to commence international operations.

By the end of 2009, both Kingfisher and Jet Airways held nearly identical market shares of 28 percent each. IndiGo was a distant fourth with a 12.5 percent market share, trailing Air India which had 15.1 percent. From this point, Kingfisher began to decline, but it wasn’t Jet Airways that capitalized on this, but rather the low-cost carriers (LCCs), with IndiGo capturing the largest share. Surprisingly, Jet’s domestic market share also started to fall, possibly due to a belief that it couldn’t compete with the LCCs. Concurrently, Jet Airways began shifting more of its fleet to international operations. Thanks to IndiGo’s superior fleet planning, it was able to swiftly occupy the market positions vacated by Kingfisher.

By mid-2010, IndiGo had surpassed Air India to become the third-largest domestic airline. A year later, it overtook Kingfisher to become the second-largest, and by early 2013, it had surpassed Jet Airways to become the largest domestic airline by passenger share. During this period, Jet’s domestic market share declined from 28.1 percent in 2009 to less than 26 percent by 2013. By early 2018, Jet’s domestic market share had further dropped to 17.6 percent, showing no signs of recovery. By the beginning of 2018, the new pecking order had IndiGo firmly at the top with over 40 percent market share, followed by SpiceJet with 13 percent, Air India with 12 percent, and GoAir with 8.4 percent. Vistara and AirAsia each held less than 5 percent market share.

Much like Kingfisher, Jet Airways was always a one-man show, led by its promoter Naresh Goyal. Jet Airways was synonymous with Goyal. However, as the market and competition expanded and transparency in decision-making within the aviation ministry increased, surviving with a legacy-era mindset became untenable. While getting work done efficiently was one aspect, steering an airline into profitability required a professional approach and a competent team.

Indigo never had a vision / mission statement, yet, what was IndiGo’s proposition that gave it the confidence to navigate against the known headwinds? What unique offering did it present to flyers?

IndiGo was founded on three simple but deeply ingrained concepts that were neither unique to IndiGo nor were they the first to be incorporated into the airline’s business philosophy. Airlines including Southwest, Ryanair, easyJet, and AirAsia have previously used IndiGo’s commercial proposition and operating strategies. Prior to IndiGo’s launch, airlines in India such as Air Deccan, SpiceJet, and GoAir had already implemented a low-cost model and attempted to emulate the concept of successful worldwide low-cost counterparts.

So, what did IndiGo do differently? IndiGo did not accomplish anything new, but did the same things differently. It was how it executed its basic business model that won the day. IndiGo was founded and continues to operate on three pillars: (i) on-time performance (ii) low-cost connectivity (iii) high-service standard. Strict commitment to these three pledges proved critical to its amazing success.

Key take aways

IndiGo was always conscious to communicate that low cost doesn’t mean cheap. The divergent paths of IndiGo and Jet Airways highlight the importance of achieving strategic fit by aligning internal capabilities and strategies with external market conditions. IndiGo’s success demonstrates the value of a focused low-cost strategy, operational efficiency, and financial discipline in a highly competitive market. Jet Airways’ failure underscores the risks of failing to adapt to changing market dynamics, carrying a high debt burden, and not aligning costs with revenues.

Excellent post Vinayak — sastry

Thanks Nukala, glad you liked it